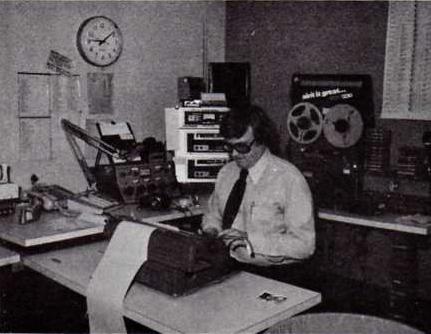

| Mike Pintek was WKBO's News

Director when a near meltdown of The Three Mile Island Nuclear plant occurred.

On March 28, 1979, while out in his Traffic Watch vehicle, Captain Dave

Edwards observed irregularities with one of the TMI cooling towers. He

immediately made some phone calls, setting into motion the drama that became

America's worst nuclear accident. Dave's discovery is part of the congressional

record of the TMI disaster. Mike Pintek, Joe Wambach and the news department

went into emergency mode and provided updates around the clock. WKBO won

numerous awards for its coverage of TMI.

Mike Pintek passed away on

September 12, 2018. Mike battled pancreatic camce since May 2017. Mike,

along with Captain Dave, broke the 3 Mile Island story on WKBO on March

28, 1979, He went to KDKA, Pittsburg, in 1982. For over 30 years he hosted

the Mike Pintek Show on KDKA. He was 65.

These picture appeared

in the April 15, 1979 issue of the Radio News Hotline

ND Mike Pintek at work in

newsroom, with LPB console, gates machines,

ampex deck and GE two-way

unit nearby. Note 'Touch-A-Matic' automatic

phone dialer near console. |

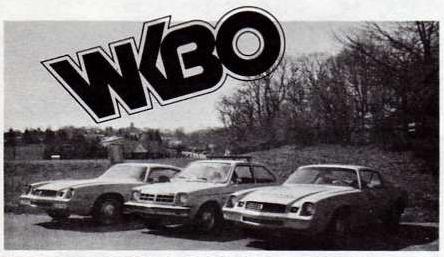

| WKBO news vehicles are

78 camaros with scanners and two-ways. "Traffic Watch" unit is 78 Chevette.

All are bright yellow. |

| WKBO Co-Anchor Michelle

Lefever working at alternate newsroom work station. |

|

"It was scary all around. It was an emotional rollercoaster."

Three Mile Island has left a permanent impact on Pennsylvania, and the

nation. Coverage of that far-reaching story presented complex problems

for local broadcasters in Harrisburg.

In this, the final part of a series, ND Mike Pintek of WKBO sums up what

happened and how you can prepare for a possible nuclear emergency

in your coverage area:

It's not like a fire. you go down to a fire and you get on your two-way

radio and say -- "yes, the buildings on fire... I can see flames leaping

throught the window.".

Well, you go down to (Three Mile) Island and it just sits there.

you really can't see anything, you have to accept everything the officials

tell you.

I think the only way you can prepare for a disaster of this sort is the

way you prepare for any other disaster. You have your telephone numbers

ready.

You could have a science editor available (either someone on your staff,

or a qualified outsider from a local college).

Another problem is one of rumors. And I think in a situation like this

you have to remain calm ... even though your own life is in danger.

You can't alarm people.

On Wednesday morning when the problem started ... the state didn't have

any monitoring equipment to go out and check on the radiation levels. So,

everybody had to depend on the power company's statements.

Turns out the legislature had not appropriated money to buy equipment.

(Met Ed) said -- everything's fine, and the state said the levels are low.

Well, you turn around and talk to a scientist and he says the levels

are high and could cause cancer.

His opinion is just as valid as the company's. Then you have the NRC (Nuclear

Regulatory Commission) coming in.

By this time, you have four or five sources of information and they're

conflicting with each other.

You have a problem then ... do I report all of these things, or what do

I do?

Well ... you don't have much of a choice, because you don't know from your

own experience or education which is right or wrong.

I think had the power company come out immediately and said-- "We have

a serious problem here" -- people would not have gotten as excited as they

did.

It was when the governor realized (and we in the mediahad already realized)

that there was conflicting information, he really started to worry.

On Friday, when people really started to get hysterical, we even

had the General Manager here ... and I had him here answering phones.

When the wire service was sending out bulletins right and left, we had

stations from all over the country calling us. The phones were jammed because

of the local calls and the phone company was at wits end trying to keep

the lines clear.

Stations wanted beepers and we had to hang up on them. I said -- I will

not tie up that newsline with calls from services from stations in San

Francisco, Los Angeles and so forth.

I think at one point somebody said to me -- "ABC News is on the line" --

and I said "I can't talk to them".

The listeners came first.

I don't

think anybody in this area really knew how to handle this story. Nobody

knew what to do. We've been through a couple of floods and we've had other

minor disasters.

It's a 20th Century nightmare! Radiation is something you can't see, you

can't feel, you can't smell ... and you don't know what it's going to do

to you.

A majority of people here at the station live within five-miles of the

plant so we had a personal stake in things. And, what do you do?

One of the big problems here was, I don't think there was ever a concerted

drive to draw up evacuation plans in the event of a disaster at the nuclear

power plant.

That's one of the good things about this incident because those plans are

drawn up now. And if it ever happens again ... God forbid ... they'll be

ready.

"This was radio's story

from the beginning. The developments were breaking so fast that radio was

the only medium that could handle it."

I was talking to a friend of mine at KDKA/Pittsburgh and he said -- "I

love this excitement".

Well, so do I. I have always loved the excitement of a good story. But

the problem is that I live here. I think the newsman has to be a

citizen too.

This was radio's story from the beginning. The developments were breaking

so fast that radio was the only medium that could handle it. We broke normal

programming, and I know that all the other stations in the area did.

I found it a very difficult story to cover. I don't know what I

would have done if this had been a one-person news operation.

We were fortunate to have four full-time people ... but that wasn't enough.

It would have been great to have twice or three-times that many. Then you

could have deployed them. |

Mike also anchored news at WASH

in Washington D.C. Mike spent over 30 years at KDKA in Pittsburgh. |